Pedro Friedeberg - Frieze

Share

It’s hard to pin down Pedro Friedeberg. The 81-year-old Mexican artist’s life has been full of contradiction, elaboration and unexpected turns, not unlike the fantastical spaces depicted in his work. Over a nearly 60 year career, the eccentric artist has defied categorization, spanning surrealism, Pop art, Op Art and furniture design, generally avoiding the style du jour and developing an oeuvre consistent only in its eclecticism. On a recent afternoon, over glasses of tequila in his Mexico City home-studio, he discussed key moments in his career, his ideas about art and originality, and the impending border wall between Mexico and the US.

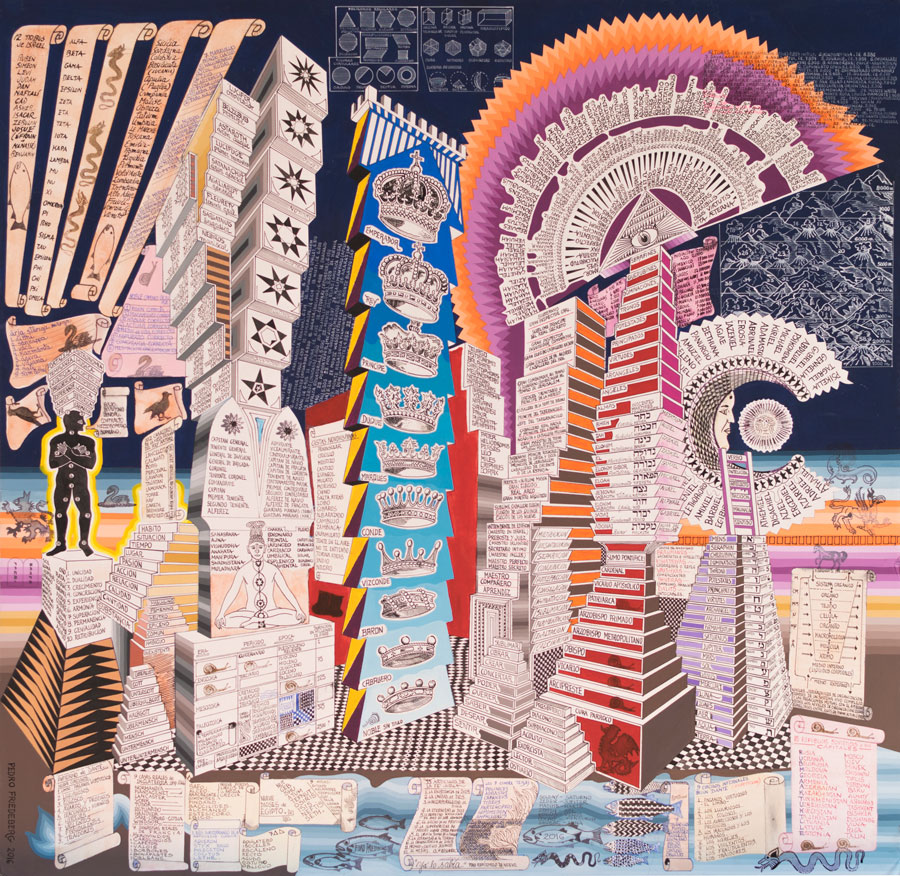

Born Pietro Enrico Hoffman Landsberg to a German-Jewish couple living in Florence, Friedeberg moved to Mexico at the age of three. Although he does not consider himself religious, he has a mezuzah – a small box containing biblical verses in Hebrew – outside his door, a gift of a friend. Hebrew characters are prominent in many of his works, as are Sanskrit and Nahuatl, each a part of a vast and inclusive cosmology.

Friedeberg has always had a great love of architecture, favouring older, ornate and ‘irrational’ building styles over the sleek geometry of modernism. He studied architecture for three years at the Universidad Iberoamericana, mostly to please his parents, before quitting his studies to pursue a career as an artist. Fantastical architectural spaces and orders appear frequently in his paintings and prints, many of which feature impossibly constructed but impeccably rendered towers, plazas, and follies, the heirs of Giovanni Piranesi, M.C. Escher and Antoni Gaudí.

The influential artist Mathias Goeritz, a fellow German émigré, encouraged and supported Friedeberg’s artistic development, even though their work could not be more different: Goeritz the stark, geometric minimalist; Friedeberg the baroque, exuberant maximalist. (They shared a love of gold.) In 1961, Friedeberg joined Los Hartos (‘The Fed-Up Ones’), a Dada-esque collective founded by Goeritz that sought to shake up what they considered the staid, conservative Mexico City art world. (They referred to him as a harquitecto, a portmanteau of the group’s name and the Spanish word for ‘architect’.) Friedeberg’s circle extended to many other prominent Mexican cultural figures of the postwar era, like Luis Barragan and Leonora Carrington. It was the legendary Mexican surrealist painter Remedios Varo who recommended him for his first solo show at Galeria Diana in 1959. For four or five years, he was an art editor for Mexico This Month, a magazine run by Anita Brenner, a writer and vocal promoter of Mexican art, considered to be Mexico’s equivalent of Gertrude Stein.

In 1962, Friedeberg created the ‘hand chair’, an open palm cupped to form a seat; it’s his best known work, and icon of ’60s design. (Its renown causes him no small amount of dismay; ‘I made furniture just to make a living, because almost nobody bought my paintings in the old days,’ he grumbles.) He continues to produce the chairs, and his home is filled with variations: there’s a massively oversized white hand chair on his roof, and smaller versions in the dining room. Some even have two thumbs, serving as arm rests. Artist Alice Rahon was so taken with the chair that she bought one and showed it to André Breton, who wrote Friedeberg a personal letter, declaring him a Surrealist.

Despite Friedeberg’s influential friends, he often worked outside of the mainstream art world, even as he flirted with its institutions. ‘Friedeberg’s punishment was to be at once famous and (until recently) excluded from the Pantheon,’ art historian James Oles has observed. This may be because critics and historians didn’t know where to place his dreamy fusion of Surrealist scenes with pop objects, Op art tricks, logotypes, mystical symbols, and pseudo-psychedelic cartoon imagery, all framed within architectural settings that pay homage to Renaissance perspective while turning it on its head. High and low, classical and novel, European, Mexican Catholic, Aztec and Asian appropriations all reside on the same plane. Humor is central to this work, and an irreverent streak slyly undermines the architectural orders and academic art history Friedeberg quotes with feverish intensity.

When asked about the border wall proposed by US President Donald Trump, Friedeberg considers it as he might an artwork. ‘In medieval times, everything had a wall around it, but a nice wall, not a plastic one,’ he says. ‘Maybe there should be a wall around each state. How many states in Mexico, 32? It would be nice to have a wall around Durango, Xacatecas... Imagine a wall separating Montana, Idaho.’ The linear symbol of Trump’s jingoism so simply becomes an absurd, ornamental maze. Might Christo be a good choice to design the wall? ‘His are just one colour,’ Friedeberg replies. ‘They’re no fun.’